Control groups (or cgroups) are a feature of the Linux kernel by which groups of processes can be monitored and have their resources limited. For example, if you don’t want a google chrome process (or it’s many child processes) to exceed a gigabyte of RAM or 30% total CPU usage, cgroups would let you do that. They are an extremely powerful tool by which you can guarentee limits on performance, but understanding how they work and how to use them can be a little daunting.

There are 12 different types of cgroups available in Linux. Each of them corresponds to a resource that processes use, such as the memory cgroup.

Before we actually dive into cgroups, there’s a few bases we should cover. Cgroups specifically deal with processes which are a fundamental piece of any operating system. A process is just a running instance of a program. When you want to run a program the Linux kernel loads the executable into memory, assigns a process ID to it, allocates various resources’ for it, and begins to run it. Throughout the lifetime of a process the kernel keeps track of its various state and resource usage information.

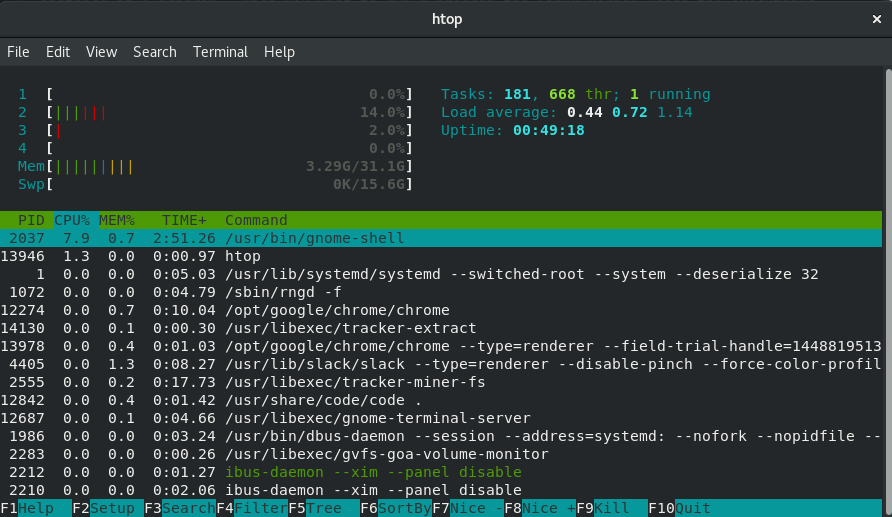

You can see all the processes running on your system and some of their resource statistics with the top command (I prefer htop).

an htop screenshot

an htop screenshot

So what do I actually mean that a process needs resources? To give some examples: In order to store and use data, a process needs to have access to memory. In order to execute it’s instructions, a process needs to have available time to run on the CPU. A process may also need access to devices, such as saving files to disk or taking in keyboard input. Each of these resources are abstracted by the Linux kernel. Those abstractions are called ‘subsystems’.

One such example of a subsystem is the virtual memory management system. This is the layer between the memory management unit (hardware) and the rest of the kernel. When the running program allocates memory for a new data structure (through something like malloc) there is functionality in the kernel to resize the heap of that process. All processes on a system share a single pool of memory that can be allocated for each of their use. As you often see if you use any electron application, a process can seriously hog all your memory.

In the screenshot above take a look at the MEM% column. That reflects the usage of total shared memory that the process is using.

CPU time is similarly a shared resource. We’re going to be using the CPU cgroup and it’s associated subsystem, the scheduler, as an example to show how cgroups work.

As fast as processors are, there is a limit to how much work they can do. For each core that your CPU has, only one process can be running at a time. However, try entering the command ps -e | wc -l. The printed number is the amount of living processes on your system. Since that number is likely in the hundreds, how can they all run considering your CPU may only have four cores?

This is accomplished with a scheduler. On a typical system every process alternates between being run and being paused. This continues for the lifetime of every process. The scheduler is the piece of the Linux kernel that decides what process to run or to pause and when.

The simple but important thing to note here is that the CPU% that you see in a program like htop refers to the percentage of time that the process is running on the CPU as opposed to paused. In other words, the more a process is scheduled to run, the higher it’s utilization of CPU, and therefore the less utilization of CPU that other processes can have.

That hopefully makes enough sense but you may be wondering how the scheduler decides what processes to schedule on and off. The default scheduler in most Linux distros is called the Completely Fair Scheduler. If the name is any indication, every process gets an equal amount of time to run on the CPU. This is generally true!* However, there are a few words missing. In truth, every process within the same cgroup gets an equal amount of time to run on the CPU.

As the name cgroup implies, we’re controlling groups of processes. Every process within a CPU cgroup enjoys equal time of the CPU. It is that group that the processes are in that defines the amount of available processor time.

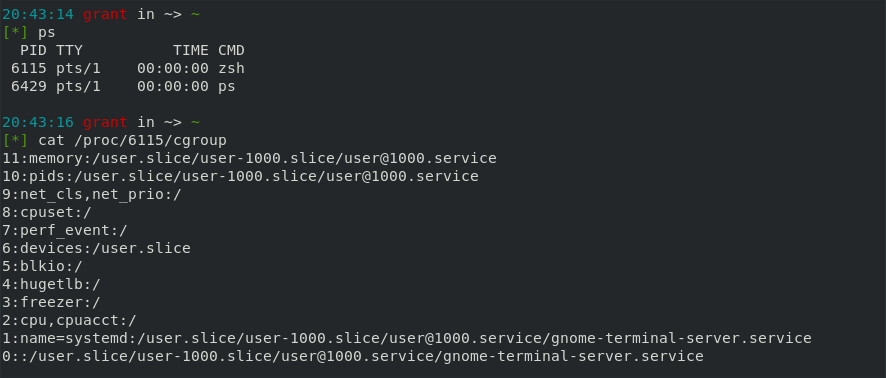

Try taking a look at /proc/[pid]/cgroup file for any process to see what cgroups it’s in. For example I wanted to see what cgroups my running shell (pid 6115) belongs to, so I read /proc/6115/cgroup:

example of listing what cgroups a process belongs to

example of listing what cgroups a process belongs to

Each line refers to a different cgroup that the process belongs to. Just looking at cpu,cpuacct (combined as just cpu) we can see that it’s in the / or “root” cgroup. This just means that it’s in the system wide cgroup that all processes belong to. Cgroups are organized in a hierarchy, so cgroups can have child cgroups. For this reason cgroups are named by their parent to child hierarchical path. For example, /cgroupA/cgroupB means there’s a cgroup called cgroupB which is a child of cgroupA which is a child of the root cgroup. The limits of parent cgroup’s apply to their children all the way down.

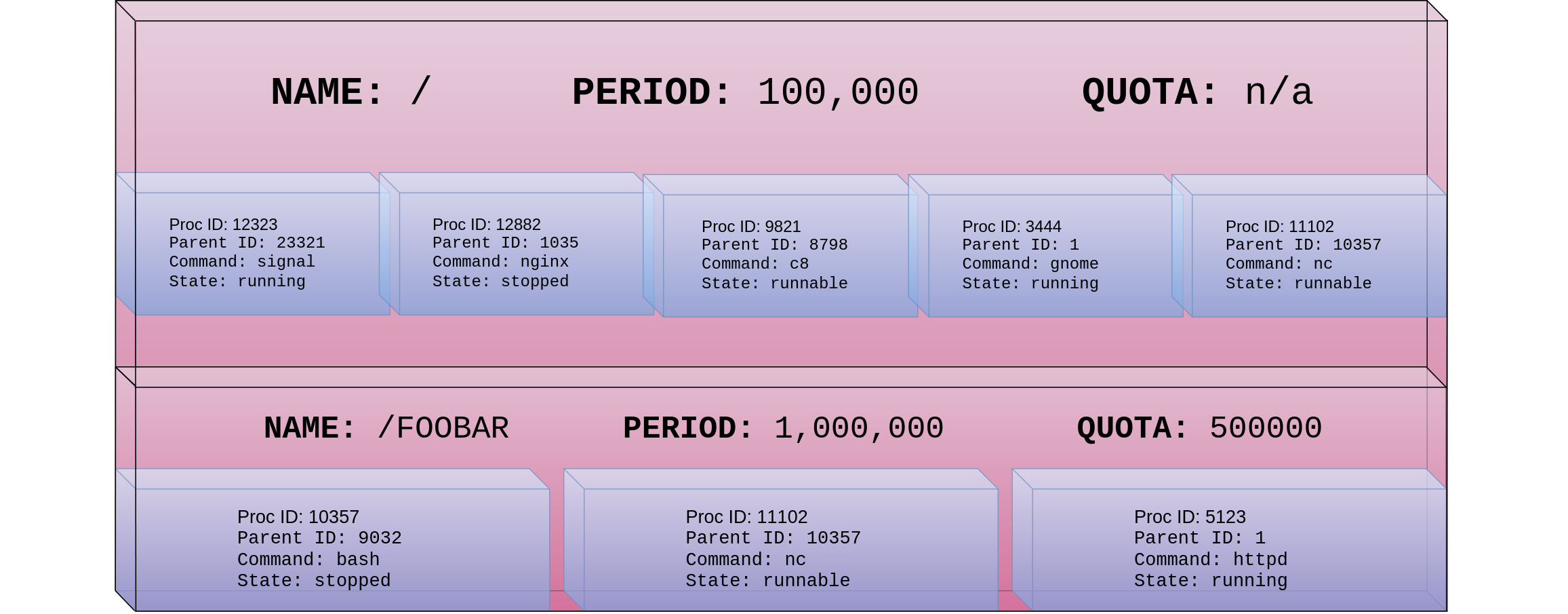

The semantics for setting these limits is pretty intuitive. There are two values that must be set: A period and a quota. Each of these values are in units of microseconds. The period defines an amount of time before the pool of available CPU ticks refreshes. The quota refers to the number of CPU ticks available in that pool. This is best explained by example:

A CPU cgroup “FOOBAR”, a child of the root CPU cgroup

A CPU cgroup “FOOBAR”, a child of the root CPU cgroup

In the diagram above we see that there are three processes in a cgroup called /Foobar. There are also many processes in the / cgroup. As we see in that root cgroup, a quota of -1 is a special value to indicate there is an unlimited quota. In other words, no limit.

Now let’s think about the /Foobar cgroup. A period of 1000000 microseconds (or one second) has been specified. The quota of 500000 microseconds (or a half second) has also been set. Everytime a process in the cgroup spends a microsecond of time running on the CPU, the quota is decremented. Every process in the cgroup shares this quota. As an example let’s say all three processes run at the same time (each on their own core) starting at the beginning of a period. After around .17 of a second the processes in the cgroup will have spent their entire quota. At that point the scheduler will opt to keep all three of those processes paused until the period is over. At that point the quota is refreshed.

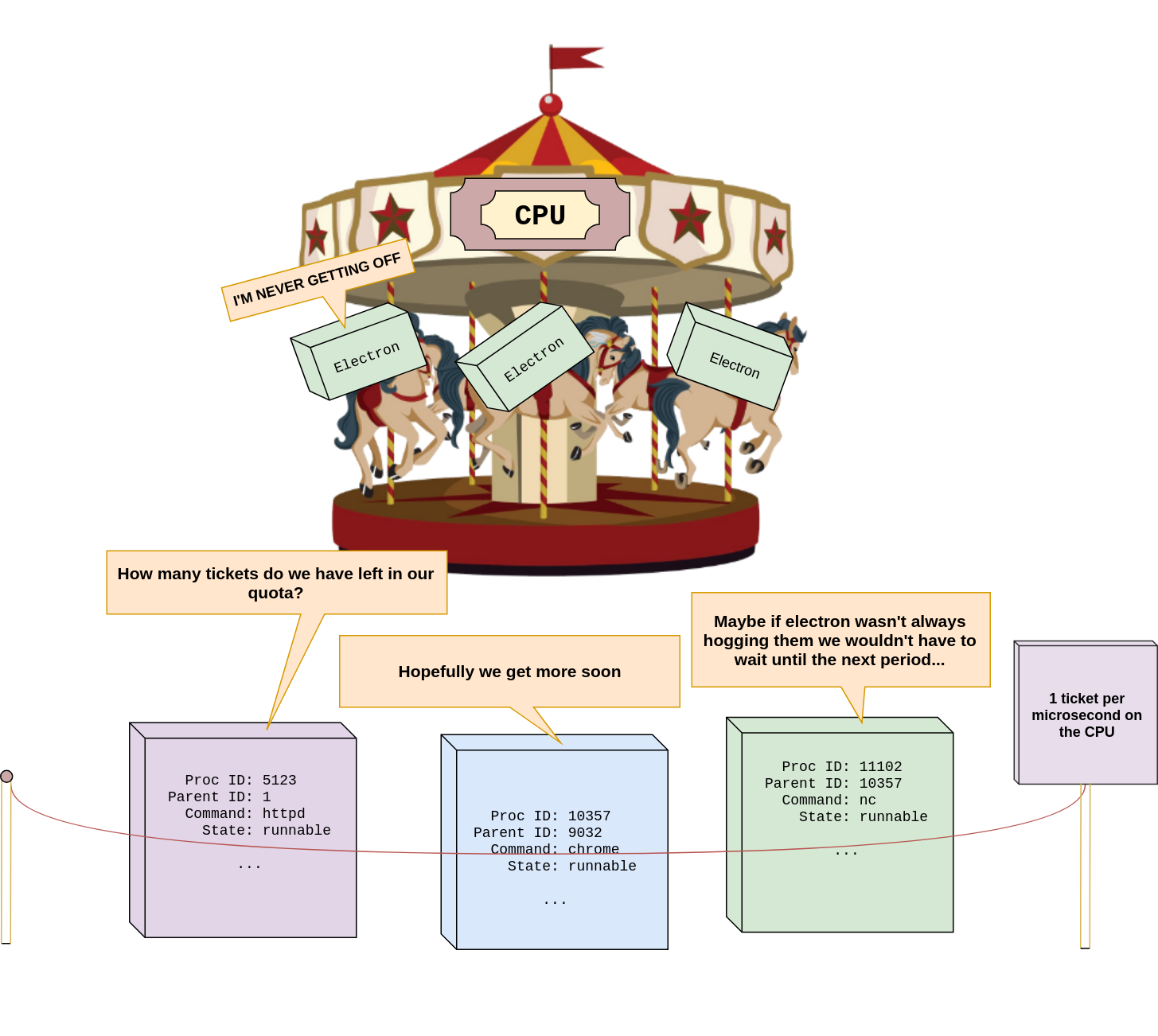

The analogy I use to explain this is to picture the CPU as if it’s an amusement park carousel. A group of processes have pooled their tickets together so they can ride on it together. They each get a daily allowance for tickets in the morning so once they run out for the day they have to wait until tomorrow. The scheduler is the person collecting tickets and cgroup is the person giving them the ticket allowance in the morning.

Here’s a really dorky graphic:

a really dorky graphic

a really dorky graphic

The purpose of explaining how the CPU cgroup works is to show the nature of what cgroups are. They are not the mechanism by which resources are limited but rather just a glorified way of collecting arguments for those resource limits. It’s up to the individual subsystems to read those arguments and take them into consideration. The same goes for every other cgroup implementation.

Using cgroups

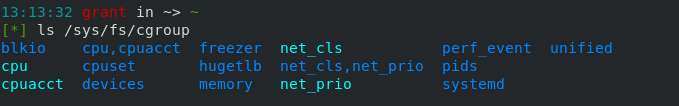

All cgroup functionality is accessed through the cgroup filesystem. This is a virtual filesystem with special files that act as the interface for creating, removing, or altering cgroups. You can find where the various cgroupfs’ (one for each cgroup type) on your system is mounted using mount | grep cgroup. They’re typically in /sys/fs/cgroup.

A cgroupfs directory for each cgroup type

A cgroupfs directory for each cgroup type

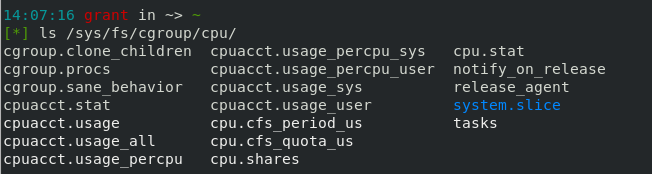

Continuing to use the CPU cgroup as an example, let’s take a look at the hierarchy and constraints for the CPU cgroup. Within the CPU directory there are a bunch of files that are used for configuring the constraints of processes in the cgroup. Since cgroups exist in hierarchies, you can also find directories that correspond to child cgroups. Making a new child cgroup is as simple as using mkdir. All the constraint files will be created for you!

Creating a child cpu cgroup using mkdir and writing a process to the tasks file

Creating a child cpu cgroup using mkdir and writing a process to the tasks file

When you’re in a child CPU cgroup there’s three main files that are of interest: tasks, cpu.cfs_period_us, and cpu.cfs_quota_us.

tasks - list of PID’s that are part of the cgroup. Appending a PID to this file will add that process (all threads in the process) to the cgroup. When you start a process it will automatically be added to the root CPU cgroup.

cpu.cfs_period_us - a single integer value representing the period of the cgroup in microseconds. The root cpu cgroup defaults to 100000 (or a tenth of a second).

cpu.cfs_quota_us - a single integer value representing the quota of the cgroup in microseconds. The root cpu cgroup defaults to -1, meaning no limit.

Setting the above constraint files are also as easy as writing values to the files:

Setting the period and quota of a cgroup by writing to the period and quota files

Setting the period and quota of a cgroup by writing to the period and quota files

Practically using cgroups

So up until this point you be wondering how people actually set cgroup limits, or why they would in the first place. Those are very valid questions! In truth, I don’t think anyone is manually creating cgroups for anything besides educational purposes.

Engineers at Google made and have been using cgroups since around 2007 to run all of their workloads side by side. If I were to guess I’d say most production systems do the same, except in varying forms. For example, today many people either use or talk about using ‘containers’. Most container runtimes ‘contain’ using cgroups as one of their main mechanisms for isolation.

If you use docker you can set cgroup constraints as flags when running containers. For example docker run –cpu-period=100000 –cpu-quota=12345 -it fedora bash. This will handle setting up the cgroup, but interestingly all it’s doing is writing to the files for you.

Setting the period and quota of a cgroup by passing flags for a docker container

Setting the period and quota of a cgroup by passing flags for a docker container

While I didn’t cover every different kind of cgroup, or even go deep into how the CPU cgroup is implemented, I hope this gives any necessary understanding about one of my favorite features of the kernel! Thanks so much for reading, please feel free to reach out for question or comment!