If you’re used to developing software in a high level language like Go or Java you likely haven’t thought about supporting different operating system versions. Sure you want to be able to run on Linux, Macos, or Windows, but that’s abstracted away for you.

When developing eBPF software you must think about hundreds of Linux kernel versions. When your eBPF programs are reading in kernel data structure fields, there’s no guarantee of backwards compatibility or stable APIs. Take a look at this example:

In Linux version 4.18, to get the pid of a process within a PID namespace you would read fields in the following order:

task_struct->group_leader->pids[PIDTYPE_PID].pid->numbers[LEVEL].nr

but starting in kernel 4.19 this data was moved to:

task_struct->group_leader->thread_pid->numbers[LEVEL].nr

You don’t have to know what any of these fields are. They’re to show that things change and it’s a lot to keep track of.

Ok, so relevant data structures change from kernel version to version, how do you handle this?

The fragile tedious way

Check out this snippet of code from tracee:

#if (LINUX_VERSION_CODE < KERNEL_VERSION(4, 19, 0)

// kernel 4.14-4.18:

return READ_KERN(READ_KERN(group_leader->pids[PIDTYPE_PID].pid)->numbers[level].nr);

#else

// kernel 4.19 onwards, and CO:RE:

struct pid *tpid = READ_KERN(group_leader->thread_pid);

return READ_KERN(tpid->numbers[level].nr);

#endif

}

Here we have a simple example where we use macro’s we defined for checking kernel versions at runtime. This is somewhat effective but cumbersome to maintain.

Enter CO:RE (or ’the better way')

What if we could read from kernel data structures without having to worry about changes in their definitions? That is the promise of ‘CO:RE’ or ‘Compile Once, Run Everywhere’.

This works by replacing libbpf helper functions like bpf_probe_read which reads from kernel memory to the stack. Instead you can use bpf_core_read. This helper uses offset relocation for source address using clang’s __builtin_preserve_access_index(). A simple explanation of how it works is that the helper uses kernel debug info (BTF) to find where kernel structure fields have been relocated to. For an actual in depth explanation of how this works, check out Andrii Nakryiko’s blog post on the subject.

Adding this support to Tracee

One of the goals of tracee is to support major distributions such as RHEL, Centos, Fedora, Ubuntu, and Debian. Not every current release of each of these distributions supports CO:RE out of the box. The RHEL based distributions have BTF support back ported all the way back to kernel 4.18. At the time of writing this, Ubuntu and Debian BTF support exists in latest releases only.

The takeaway from this is that we need to support both CO:RE and non-CO:RE version of tracee. The rest of this blog post is a write up of how we did just that.

vmlinux.h

The first thing we needed to do was generate a vmlinux.h file. I wrote a dedicated post about the subject but i’ll summarize. It contains all the kernel data structure definitions of a particular kernel. We generated a single vmlinux.h file and committed it to source control. All the kernel data structure accesses in tracee bpf code use those definitions.

Updating our kernel-read macro

Tracee defines a custom macro for reading data structures named READ_KERN. You can see it used above. Before recent CO:RE changes it’s definition looked like this:

#define READ_KERN(ptr) ({ typeof(ptr) _val; \

__builtin_memset(&_val, 0, sizeof(_val)); \

bpf_probe_read(&_val, sizeof(_val), &ptr); \

_val; \

})

All the CO:RE changes did was change bpf_probe_read to bpf_core_read:

#ifndef CORE

#define READ_KERN(ptr) ({ typeof(ptr) _val; \

__builtin_memset(&_val, 0, sizeof(_val)); \

bpf_probe_read(&_val, sizeof(_val), &ptr); \

_val; \

})

#else

#define READ_KERN(ptr) ({ typeof(ptr) _val; \

__builtin_memset(&_val, 0, sizeof(_val)); \

bpf_core_read(&_val, sizeof(_val), &ptr); \

_val; \

})

#endif

You can see that we use a compile time variable called “CORE”. That’s passed via clang using -DCORE. You can use bpf_core_read directly or even better yet BPF_CORE_READ/BPF_CORE_READ_INTO from libbpf.

One important thing to note is that, as a result of this change, we had to un-nest successive calls of READ_KERN. Under the hood bpf_core_read() applies the clang function __builtin_preserve_access_index() which causes the compiler to describe type and relocation information. You cannot nest calls to __builtin_preserve_access_index() so we ended up with changes like this:

static __always_inline u32 get_mnt_ns_id(struct nsproxy *ns)

{

return READ_KERN(READ_KERN(ns->mnt_ns)->ns.inum);

}

turned into:

static __always_inline u32 get_mnt_ns_id(struct nsproxy *ns)

{

struct mnt_namespace* mntns = READ_KERN(ns->mnt_ns);

return READ_KERN(mntns->ns.inum);

}

Missing Definitions Header

The generated vmlinux.h does not contain the the macros or functions that you’d find in system header files. For example, we want to use TASK_COMM_LEN which is found in linux/sched.h. Another example is the function inet_sk from net/inet_sock.h.

I had a conversation on the mailing list asking how to handle this. The unfortunate reality is that we have to maintain a header file where we redefine macros and functions that tracee relies on.

Hopefully something like the __builtin_is_type_defined suggested in that thread list can be implemented in clang but until then a missing macros header is the way.

Again, refer to my vmlinux.h blog post for more information.

Verifier Compalints

There were a few verifier issues that we ran into which blocked us for some time. The bpf verifier output is decipher but that’s nothing unique to CO:RE.

Take another look at our definition of the READ_KERN function macro:

#define READ_KERN(ptr) ({ typeof(ptr) _val; \

__builtin_memset(&_val, 0, sizeof(_val)); \

bpf_core_read(&_val, sizeof(_val), &ptr); \

_val; \

})

Notice how every time READ_KERN is called, another variable is allocated. In loops that get unrolled, there’s no optimization to reuse the same variable. As a result it’s very easy to exceed the 512 byte stack limit. The strange thing is that the bpf_probe_read version of READ_KERN did not cause the stack limit to be exceeded, but bpf_core_read did. I never confirmed what causes this but I assume it has to do with stack spillage as a result of the relocation code. We mitigated this by optimizing loops to reuse variables that are defined before the loop starts.

Note that this same performance hit applies if using BPF_CORE_READ/BPF_PROBE_READ as the definition is similar to READ_KERN.

Distribution

The CO:RE version of tracee can be compiled in any environment, regardless of if BTF is enabled in it’s kernel. This is because we version controlled the vmlinux.h file. As a result, the CO:RE enabled bpf object is always built with tracee. When the userspace Go code is compiled, we embed this bpf object using Go’s embed directive. At runtime tracee detects if BTF (and therefore CO:RE) is supported, in which case it runs the CO:RE object. Otherwise it looks for a kernel specific bpf object, or attempts to build one.

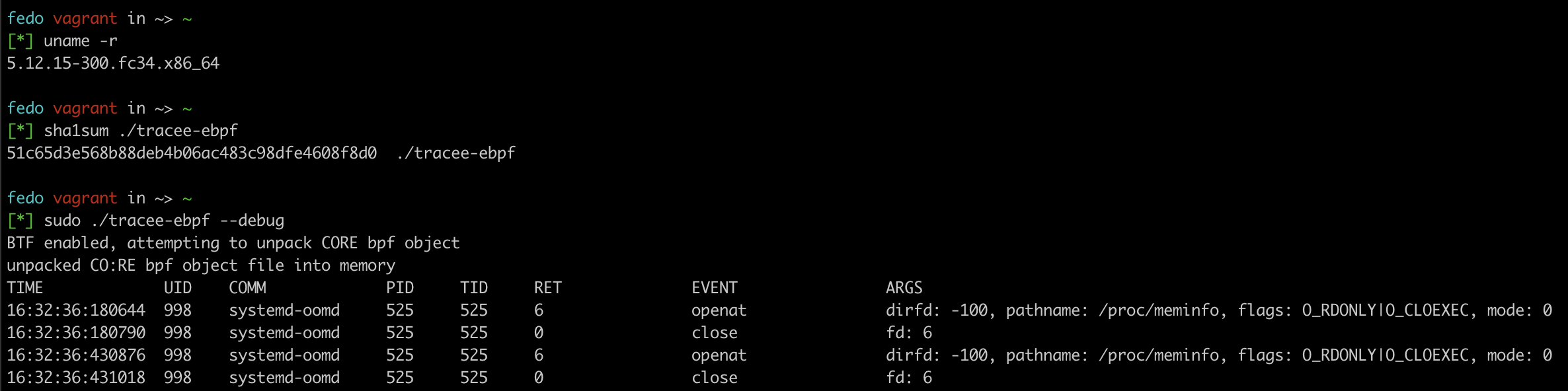

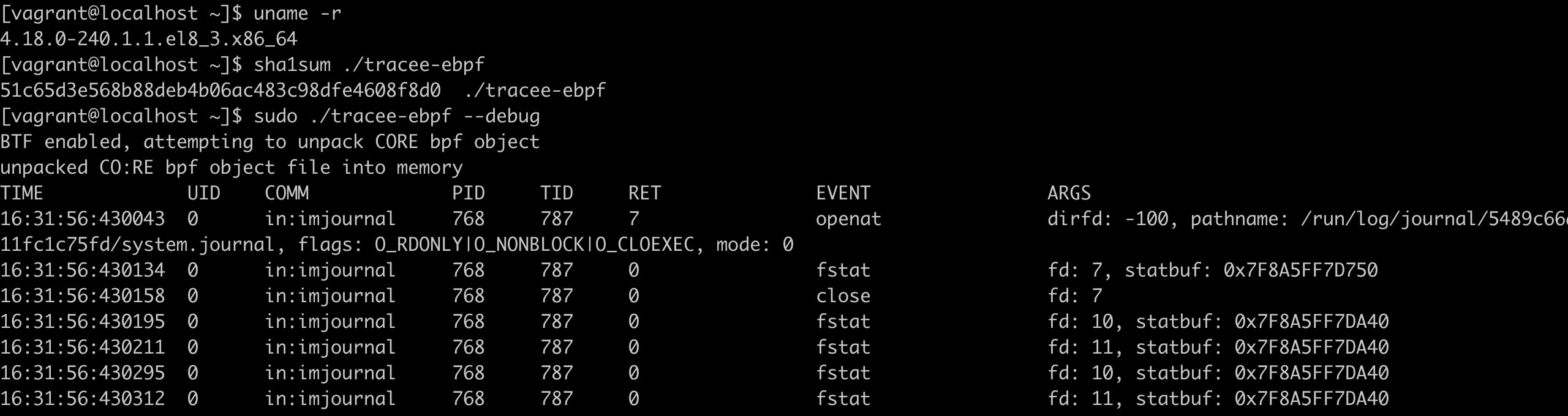

It works!

Here we can see the same CO:RE enabled BPF object file running perfectly on a 5.12 kernel, and a 4.18 one!