The Linux kernel is the biggest open source project in existence. It has tens of thousands of contributors from all around the world, from many different companies and communities.

Linux development does not happen in a single github repository, and likely never will. Instead there are many forks of the linux kernel. Development happens in these forks for very specific subsystems, only a fraction of the overall code. Contributors submit relevant patches to the ‘mailing list’ that is used for each of these forks. The fork maintainers review these patches, and at regular intervals submit groups of patches ‘upstream’ to more generalized forks. All these patches eventually make their way up to the ‘mainline’ kernel which a single maintainer presides over. Eventually the forks pull down the changes from other downstream forks.

It’s a huge task to keep track of this whole system at once but luckily as an individual contributor, you don’t need to. Once you know what subsystem community you’d like to be a part of, you can find the correspond mailing list.

Mailing lists are where kernel developers discuss ideas, and submit patches. Mailing lists are not much more than an email forwarder. You send an email to the mailing list, and then everyone who is subscribed to the mailing list gets your email. It’s an intimidating system so let’s dive into how to start using it.

Subscribe

You can subscribe to the mailing list of your choice using majordomo (a mailing list manager). You can find the many lists for the various subsystem communities here. You can find instructions here for subscribing, but essentially you want to send an email to majordomo@vger.kernel.org with the body of your email saying only subscribe <list-name> (where list name would be replaced by something like ‘bpf’). You can unsubscribe the same way.

Using gmail

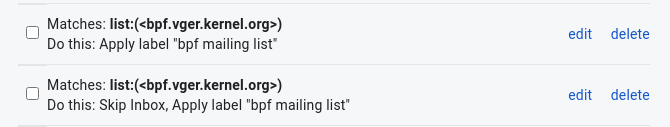

Once you subscribe to a mailing list, your inbox will quickly be consumed by a deluge of emails. There are a few ways to organize this, but I like to have each mailing list in their own label and not in my inbox. I create a label (via settings), and add filters like so:

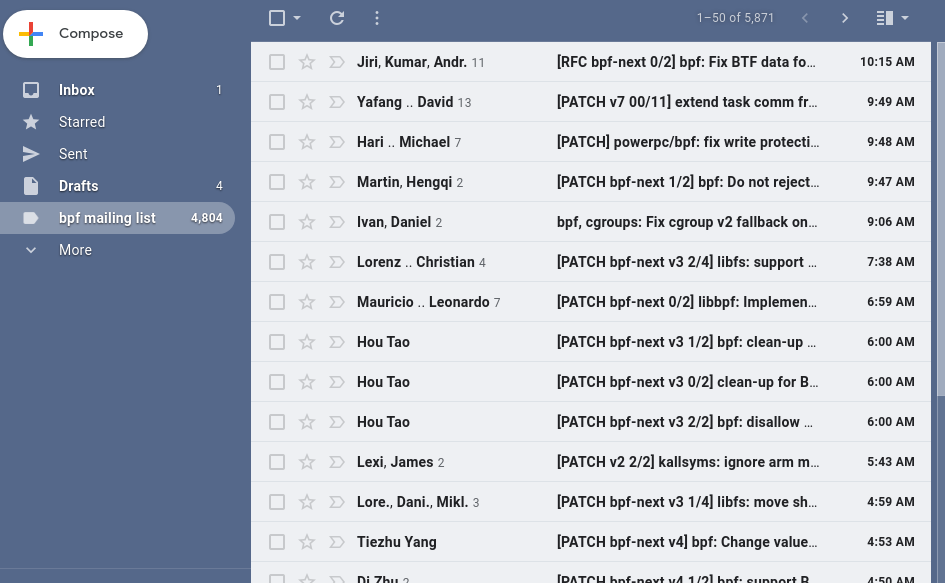

This way my inbox looks like this:

Participating in conversation

Code of conduct

The linux kernel community has a bad reputation. I haven’t experienced any toxicity but have seen evidence of it. There is a code of conduct that absolutely should be followed and enforced. You should always feel safe to be part of the linux community and accept that you’re allowed to make mistakes.

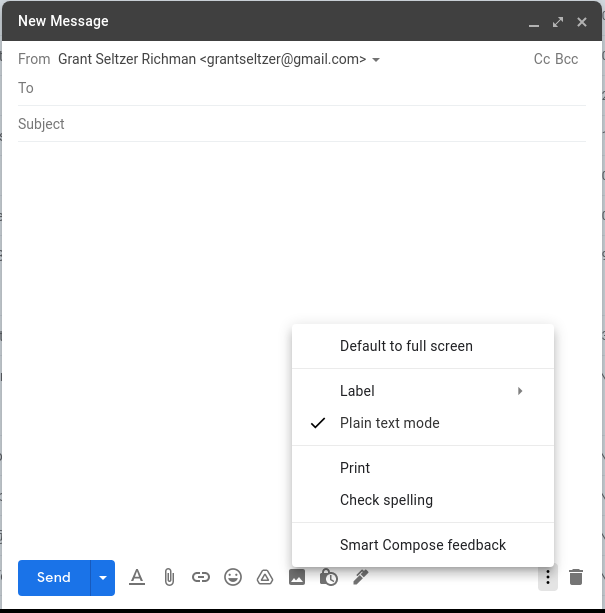

Plaintext

The mailing lists require you to only use plain text as opposed to HTML. If you fail to turn on plain text mode, your email will likely be rejected.

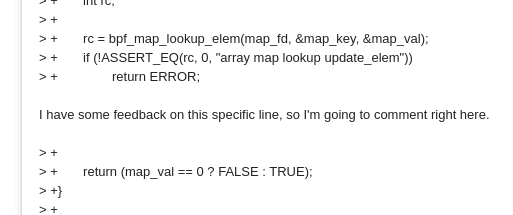

Bottom posting

Conversation on the mailing list is formatted a little different from normal email conversations. To make it obvious what your message is specifically in response to, your messages should be placed underneath the previous email. Hit ‘reply-all’, then expand the full reply message, scroll down to the part of the previous message or patch that you want to reply to, and write your post there. You can and should reply in multiple places as well.

Formatting patches

Patches can actually be submitted via git on the command line. There are a few workflows that you can use but this is how I like to do it.

First, make your code changes.

Next, make your commits with meaningful commit messages. You can find a good guide on how to properly format your commit message here. You can do a git log to take a look at examples. Seperate each commit logically

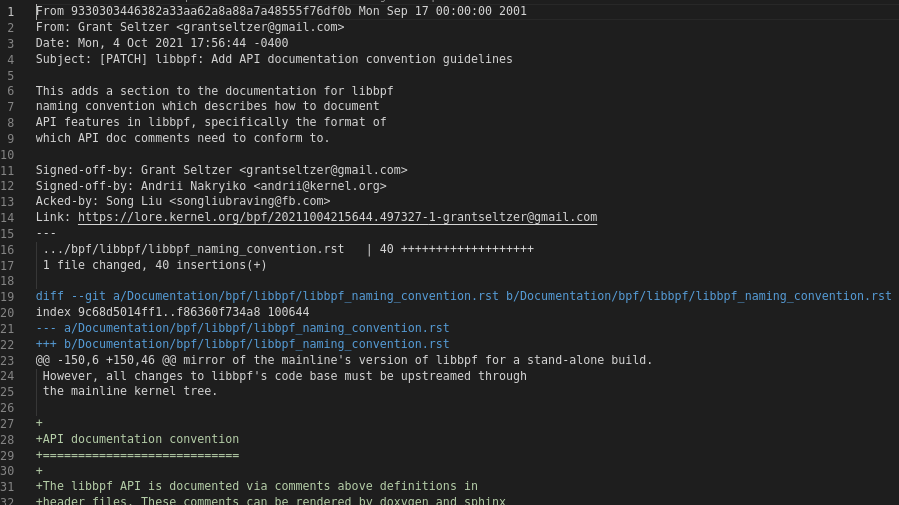

Next, you’re going to format a patch or series of patches. A patch is a file which contains a plaintext representation of a commit, as well as headers to be interpreted for an email client, such as gmail. Here’s what that looks like:

The patch file is created using git, and sent to the mailing list using git.

To create a patch, you use git format-patch. You can specify specific commits with this to generate patch files. If your changes span multiple commits, you would create one patch file for each commit. For example:

git format-patch HEAD~1

This would create a single patch file out of the most recent commit. If you made 3 commits that you want to submit as a single patch series, you would do HEAD~3 instead. The file will be created in your current working directory named something like “0001-libbpf-Add-API-documentation-convention-guidelines.patch”. The 0001 is just the number of the patch file in the order it was created. The rest of the name is the subject line of the commit message.

Next, there’s a script for checking to see if you made any simple mistakes in formatting your patch/commit message. You can run from the base of the linux repo like so:

[*] ./scripts/checkpatch.pl 0001-libbpf-Add-API-documentation-convention-guidelines.patch 130 ↵

total: 0 errors, 0 warnings, 46 lines checked

0001-libbpf-Add-API-documentation-convention-guidelines.patch has no obvious style problems and is ready for submission.

Correct any problems that the script points out, and then you’re ready to send it!

Submitting patches

Now that you have your patch file(s) you can send them to the mailing list via email. Git has a useful command for doing exactly this.

First you need to set up git to use gmail. A very helpful guide can be found here. It’s just a matter of setting up gmail as your git smtp server.

Here’s an example command:

[*] git send-email ./0001-my-changes.patch --to maintainers-name@kernel.org --cc mailing-list-name@vger.kernel.org

The only arguments that git send-email takes are the paths to patch files. If you’ve created a multiple patch set, invoke the command once with all of them specified. Then you pass recipients via the to and cc flags. You should of course include the mailing list and specific maintainers which you can get by invoking the scripts/get_maintainers.pl script.

Note

I was very intimidated making my first contribution but I had the help of some very kind people who patiently walked me through the very contents of this guide. If you’re ever worried or intimidated about using the mailing list, I would be more than happy to help you with it, you can always reach out via email.