In my previous posts on the subject of bpf I used a project called BCC to compile, load, and interact with my bpf programs. I, and many other developers, have recently heard about a better way to build ebpf projects called libbpf. There are a few good resources to use when developing libbpf based programs but getting started can still be a quite overwhelming. The goal of this post is to provide a simple and effective explanation of what libbpf is and how to start using it.

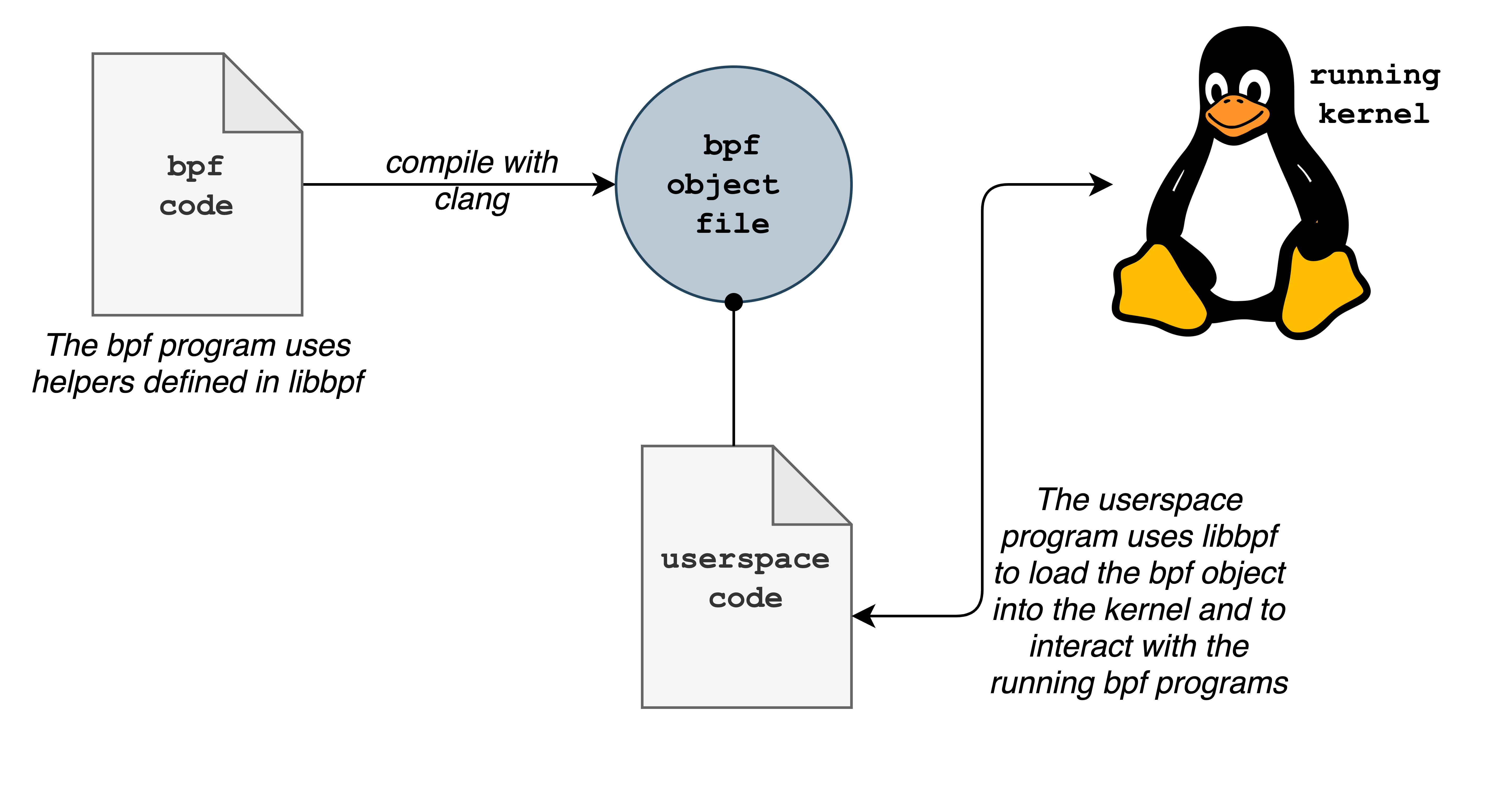

libbpf is library that you can import in your userspace code. It also contains helpers that you can use in your bpf programs. In userspace, It provides developers with an API for loading and reading output from bpf programs. It is maintained in the linux kernel source tree which makes it a very promising package to rely on.

In order to illustrate the nature of libbpf and how to use it, we’re going to write a simple bpf program that tells us everytime a process uses the execve system call (via the __x64_sys_execve kernel function). We’re then going to write a userspace program, in Go, which loads the compiled bpf program and listens for output from it.

Kernel side

Let’s start with the imports:

#include "vmlinux.h"

#include <bpf/bpf_helpers.h>

#include "simple.h"

As you might assume, bpf_helpers.h contains a lot of useful functions for you to use in your bpf programs. As for vmlinux.h, I wrote a complementary blog post on the subject, you can find it here.

Now we’re going to need a way to transmit output to userspace everytime the bpf program is called. For this we’re going to set up a ringbuffer:

struct {

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_RINGBUF);

__uint(max_entries, 1 << 24);

} events SEC(".maps");

There are many types of maps you can use in bpf programs. Ringbuffers are a reliable way to transport data from kernel space to user space. If this isn’t the first bpf program you’ve written, you’ve likely also seen perfbuffers. In the blog post I linked above you can read about the benefits of using ringbuffers instead of perf.

We’re going to transmit an ’event’ over the ringbuffer whenever our bpf program is called, so we’ll just define that as a struct like this:

typedef struct process_info {

int pid;

char comm[TASK_COMM_LEN];

} proc_info;

Finally, let’s look at the actual bpf program:

SEC("kprobe/sys_execve")

int kprobe__sys_execve(struct pt_regs *ctx)

{

__u64 id = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid();

__u32 tgid = id >> 32;

proc_info *process;

// Reserve space on the ringbuffer for the sample

process = bpf_ringbuf_reserve(&events, sizeof(proc_info), ringbuffer_flags);

if (!process) {

return 0;

}

process->pid = tgid;

bpf_get_current_comm(&process->comm, TASK_COMM_LEN);

bpf_ringbuf_submit(process, ringbuffer_flags);

return 0;

}

The bpf program itself is just this function, it’s essentially main(). We can define and import other functions of course, but those must be marked with the __always_inline attribute. This is to limit complexity and avoid any recursion as bpf programs must terminate!

So, let’s break this down.

SEC("kprobe/sys_execve")

This is the section macro (defined in bpf_helpers.h). All programs must have one to tell libbpf what part of the compiled binary to place the program. This is essentially a qualified name for your program. There isn’t a strict rule for what it should be but you should follow the conventions defined in libbpf. You can also see the SEC label above in the ringbuffer definition.

int kprobe__sys_execve(struct pt_regs *ctx)

Here we can see that the program name is kprobe__sys_execve. You can name it whatever you like and use this name as an identifier from the userspace side. Every different type of bpf program has its own ‘context’ that you get access to for use in your bpf program. A good breakdown on the different things you can attach bpf programs to and what context is available for them can be found here.

In the case of this kprobe bpf program we have a struct pt_regs which gives us access to the virtual registers of the calling process. Alternatively you can use the BPF_KPROBE macro which will extract arguments for you so you don’t have to parse the struct pt_regs manually!

After this, it’s mostly self explanatory:

__u64 id = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid();

__u32 tgid = id >> 32;

proc_info *process;

// Reserve space on the ringbuffer for the sample

process = bpf_ringbuf_reserve(&events, sizeof(proc_info), ringbuffer_flags);

if (!process) {

return 0;

}

process->pid = tgid;

bpf_get_current_comm(&process->comm, TASK_COMM_LEN);

bpf_ringbuf_submit(process, ringbuffer_flags);

return 0;

We’re reserving space for a struct process_info on the ringbuffer, reading in the process ID, and the process name for it, and submitting it on the ringbuffer, that’s it!

Userspace side (libbpfgo)

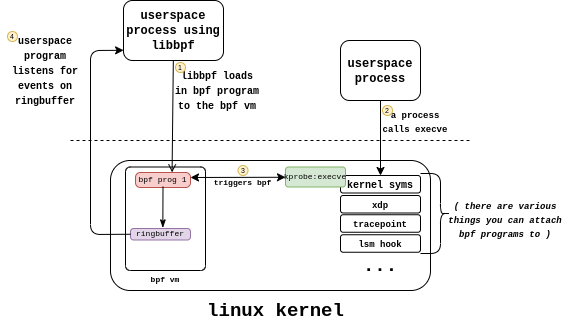

Our goal for the userspace program is to load the compiled bpf program, attach it to the appropriate kprobe, listen for the output from the ringbuffer, and clean things up when we’re done.

Since libbpf is a C library it’s simple to create bindings for it in higher level languages, like Go. If you’d like to write your userspace code in pure C, you can follow this post.

The first step is to compile the bpf code into an object file:

clang -g -O2 -c -target bpf -o mybpfobject.o mybpfcode.bpf.c

Now we can use libbpfgo, a thin wrapper around libbpf itself. The goal of libbpfgo is to implement all of the public API of libbpf so you can easily use it from Go. We’ve started with the features that tracee needs, but everything else will be coming soon!

Before we implement it in code, let’s look at a highlevel what we’re going to be doing:

We can load in the object file like so:

bpfModule, err := bpf.NewModuleFromFile("mybpfobject.o")

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

defer bpfModule.Close()

bpfModule.BPFLoadObject()

Next we can find the bpf program that we want to use (you can put multiple into a single object file), and attach it to the hook we want to, in this case the __x64_sys_execve kernel function.

prog, err := bpfModule.GetProgram("kprobe__sys_execve")

if err != nil {

panic()

}

_, err = prog.AttachKprobe("__x64_sys_execve")

if err != nil {

panic()

}

And finally we set up a go channel to use for listening to output from the ringbuffer, and print out events as they come in.

eventsChannel := make(chan []byte)

rb, err := bpfModule.InitRingBuf("events", eventsChannel)

if err != nil {

panic()

}

rb.Start()

for {

eventBytes := <-eventsChannel

pid := int(binary.LittleEndian.Uint32(eventBytes[0:4])) // Treat first 4 bytes as LittleEndian Uint32

comm := string(bytes.TrimRight(eventBytes[4:], "\x00")) // Remove excess 0's from comm, treat as string

fmt.Printf("%d %v\n", pid, comm)

}

The only other thing to note is that we have to import “C” at the top of this file.

Building looks like this:

CC=gcc CGO_CFLAGS="-I /usr/include/bpf" CGO_LDFLAGS="/usr/lib64/libbpf.a" go build -o libbpfgo-prog

So we have a couple dependencies here that we need to have, but luckily are provided by most package managers. /usr/include/bpf is the path to the libbpf source code on my system. If it’s not provided by your distribution (something like ’libbpf-dev’) you can just commit the libbpf source code in your project repository. libbpf.a can either be built manually or provided by a package (something like libbpf-dev-static). The resulting binary will be named libbpfgo-prog.

Finally, you can either run this as root or with CAP_BPF/CAP_TRACING (linux 5.8+):

[*] sudo ./libbpfgo-prog

6400 sh

6399 sh

6401 node

6403 sh

6402 sh

6404 node

...

Wrapup roundup

To review, we first wrote a bpf program using helpers defined in libbpf. The bpf program read information like the process ID and command then wrote it to a shared ringbuffer. We compiled it with clang, then used libbpfgo to load it into the kernel and listen for output from the ringbuffer.

Check out documentation for libbpfgo here, a good place to look for examples of usage would be in the tests here. All of the code written for this blog post can be found here.